The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) is a non-profit political organization representing numerous First Nations across BC in order to protect and further Aboriginal title and rights. The UBCIC has adopted a firm stance on Aboriginal title to the land, and has consistently opposed the federal government’s Comprehensive Claims Policy as well as the BC Treaty Process, as the Union argues that these are processes to extinguish and modify rights:

UBCIC logo, courtesy of UBCIC.

Since the federal government articulated its land claims policies in 1973, the UBCIC has consistently opposed the federal government’s “comprehensive claims” and “modern treaty-making” processes because they require that we surrender our Aboriginal Title and Rights in order to settle the land question. The UBCIC has always supported the people’s contention that land is more important than money in land claims settlements.1

The UBCIC identifies its role as protecting and furthering Indigenous rights, serving as a source of information for bands across the province, and building capacity for Aboriginal communities.2 The UBCIC also holds a special consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.

Since its inception, the UBCIC has established several publications, including its newspaper NESIKA, the UBCIC News, and Indian World. These publications along with frequent bulletins have played important roles in British Columbia’s political history by circulating up-to-date political information to distant and otherwise isolated Aboriginal communities. The UBCIC also serves as a central information resource for researchers and organizations, and hosts conferences and workshops along with housing a Resource Centre. UBCIC’s head office is currently located in Vancouver, with a satellite office located in Kamloops.

You can visit the UBCIC’s official website here.

How the UBCIC operates

The current President of the UBCIC is Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Penticton Indian Band. Chief William Charlie of the Stó:lo First Nation serves as Vice President, and Chief Bob Chamberlain of the Kwicksutaineuk-Ah-Kwaw-Ah-Mish First Nation is Secretary-Treasurer.

The UBCIC consists of a Chiefs’ Council and an Executive Committee. The Chiefs’ Council is comprised of chiefs from each of the member communities, and serves as the governing body of the UBCIC. The Chiefs’ Council meets at least once every three months.

The Executive Committee consists of the President, Vice President, and Secretary-Treasurer. Members of the Executive Committee are nominated and voted in by members of the Chiefs‘ Council. Each member of the Executive Committee serves a term of three years.3

The UBCIC holds an Annual General Meeting (AGM) every year in which each member band is represented, policy is examined and resolutions are passed. The UBCIC also holds Special General Meetings throughout the year as necessary.

A brief history of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs

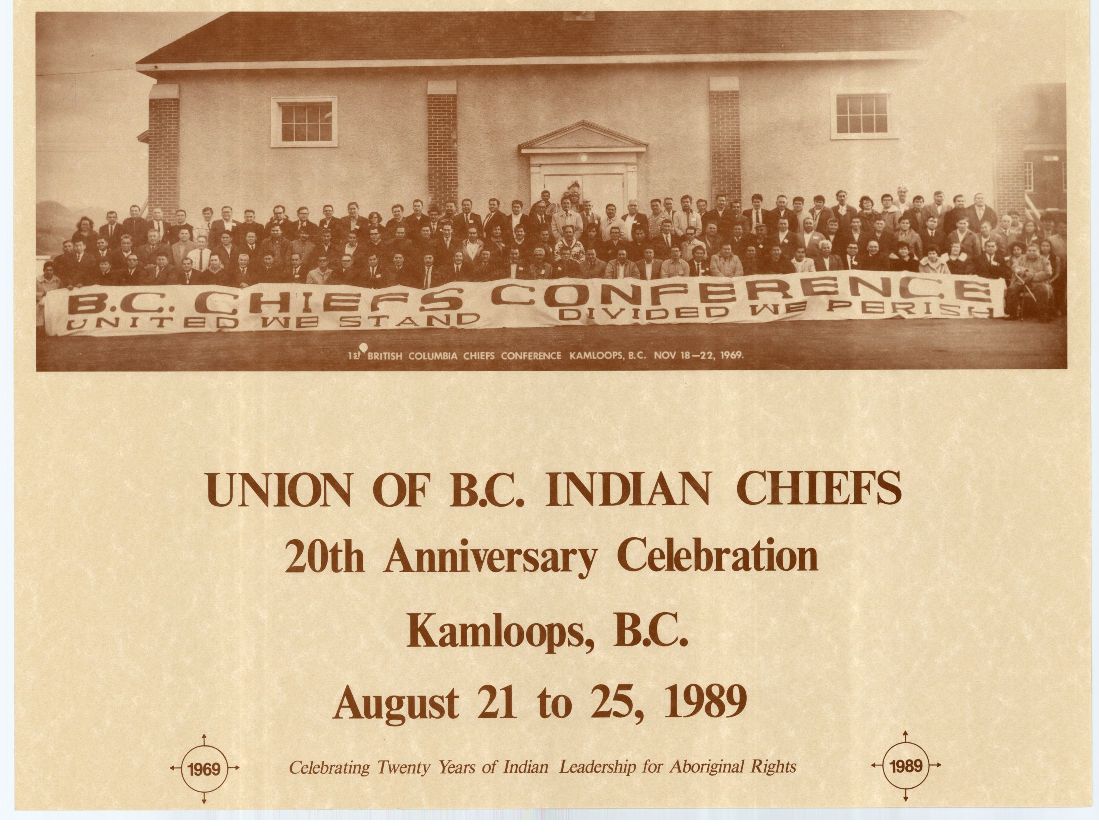

The UBCIC was founded in November 1969 when a number of chiefs across British Columbia united in response to the federal government’s proposed “White Paper,” a policy paper in which the government proposed to dismantle the Department of Indian Affairs, repeal treaties, and transfer jurisdiction of Aboriginal issues to the province. The UBCIC viewed these proposals a way to assimilate Aboriginal people into mainstream Canadian society and do away with the distinct relationship Aboriginal peoples had with the Canadian government.

Chief Dennis Alphonse of the Cowichan Band wrote letters to chiefs and political organizations across BC urging them to come together so that First Nations across the province could discuss a united response to the White Paper. With the support of Rose Charlie of the Indian Homemaker’s Association, Philip Paul of the Island Tribal Federation, and Don Moses of the North American Indian Brotherhood, a conference was organized in Kamloops. 144 Bands across BC sent representatives to the conference, making it the most “broadly representative” meeting of First Nations in BC.4 After several days of discussions, the UBCIC was formed as a means of uniting the groups to assert their Aboriginal title.

First chiefs conference, 1969. Image courtesy of UBCIC.

In 1971, at the Third Annual UBCIC convention in Victoria, the UBCIC released A Declaration of Indian Rights: The B.C. Indian Position Paper, commonly known as the “Brown Paper,” in response to the government’s White Paper. The Brown Paper was a document that rejected the White Paper policy proposals and would become the cornerstone for UBCIC’s Land Claims position on Aboriginal title to the land.5

A turning point for UBCIC: The rejection of government funding, dissolution and rebuilding.

In 1975, the Annual General Meeting at Chilliwack presented a major turning point for the organization. The UBCIC resolved to focus on title and rights on behalf of all the Indian people of BC, status or non-status. They also agreed that the executive would be voted in by the annual assembly, making the organization more democratic and less hierarchical.6

The UBCIC has archival footage of this historic AGM. Watch it here.

UBCIC members had expressed concerns that the Department of Indian Affairs maintained too much control over the lives of Aboriginal peoples by controlling funding. The UBCIC therefore passed a motion in which they resolved to reject all government funding as a step toward self-determination. Despite some concerns that this would result in major hardships faced by First Nations communities, the resolution passed based on the belief that a rejection of government funding would be a rejection of government control.7

This meant that funding for bands, education initiatives, and welfare programs were also cut off, crippling the UBCIC as well as bands around the province. In the ensuing months, many First Nations protested these drastic measures when it became starkly apparent just how dependent First Nations bands and organizations were on federal money. Some members felt that the leaders were no longer representing their members, and the UBCIC lost much of its support.8

The rejection of funding meant that the UBCIC had to make drastic cuts to staff and resources. The Union began experiencing disunity as leadership could not reach consensus on how to handle these difficult times.9 The office shut down temporarily before being reopened at Coqualeetza, near Chilliwack, BC. Steven Point and Robert Manuel took over and invited the influential leader George Manuel to join them. Manuel was then leading the National Indian Brotherhood and the World Council on Indigenous Peoples.

1980s: Renewed hope and revitalization for UBCIC

UBCIC’s 20th anniversary poster, 1989. Image courtesy of UBCIC.

In 1979, George Manuel resigned from the National Indian Brotherhood and accepted the invitation to lead the UBCIC in a new direction. Manuel created the Aboriginal Rights Position Paper (available here), a foundation of UBCIC’s philosophy. During his term from 1979-1981, Manuel began to hire and train Aboriginal staff to build capacity and sustainability amongst Aboriginal communities instead of hiring outside non-Aboriginal “experts.”10

The UBCIC helped orchestrate several direct actions, including the Indian Child Caravan in 1980, the 1981 women’s 3-week occupation of the BC Regional Office of the Department of Indian Affairs to protest the conduct of an employee, as well as the 1981 Constitution Express, which brought awareness to the need for Section 35 in the Constitution. These actions were all ultimately successful in achieving their desired outcome.

After George Manuel fell ill during the Constitution Express, Bob Manuel took over as President in 1981. Saul Terry was then elected President in 1983 and would hold it until 1998, the longest term of any UBCIC President. When Saul Terry decided not to run, Chief Stewart Phillip was elected in 1998. He continues to serve as President today.

In 2005, the UBCIC joined First Nations Summit, the BC Assembly of First Nations, and the BC Liberal government in drafting BC’s “New Relationship,” a policy that aimed to guide and establish “a new government-to-government relationship based on respect, recognition and accommodation of Aboriginal title and rights.”11 The UBCIC continues to work with and advise the provincial government policies regarding Aboriginal relations, title, and rights.

By Erin Hanson.

Recommended resources

-

- UBCIC Official website: http://www.ubcic.bc.ca

The UBCIC’s website is a valuable resource for information pertaining to First Nations in B.C. This website holds digital archives of old UBCIC newsletters, photographs, video, and makes several UBCIC publications available online including policy papers, Chief Kerry’s Moose, a guide to land use studies, Stolen Lands, Broken Promises, a guide for band researchers, Our Homes are Bleeding, a history of the reserve system, and many more.

- Follow UBCIC on Twitter: http://twitter.com/UBCIC

- View UBCIC’s Digitized Resources & Publications Portal: https://www.ubcic.bc.ca/ubcic_publications

- Nickel, Sarah A., and Scholars Portal Books: Canadian University Presses 2018. Assembling Unity: Indigenous Politics, Gender, and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. UBC Press, Vancouver, 2019 (Ebook Available Online through UBC Library)

- Manuel, Vera. “The History of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs – 20 Years of Struggle for Aboriginal Rights.” 1989.

Endnotes

1 Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC), “About.” https://www.ubcic.bc.ca/about

2 UBCIC, “Mandate.” September 10, 2010. https://www.ubcic.bc.ca/mandate

3 UBCIC, “Constitution and Bylaws,” June 2019. https://www.ubcic.bc.ca/constitution

4 Tennant, Paul. Aboriginal Peoples and Politics: The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989. 152.

5 Manuel, Vera. “The History of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs – 20 Years of Struggle for Aboriginal Rights,” 1989. 3.

6 Tennant, 178.

7 Manuel.

8 Tennant, 179.

9 Manuel.

10 Manuel, 11.

11 UBCIC, “A New Relationship.”