In this section

- Introduction

- Fishing Since Time Immemorial

- Coast Salish Harvesting Methods

- The introduction of canneries and a wage-based economy

- The creation of an Aboriginal “food fishery”

- Aboriginal fisheries in the courts: Sparrow, Van der Peet, and other legal challenges

- Not a “race-based” fishery.

- Bibliography & Recommend Resources for Further Research

- Endnotes

Introduction

In August of 2009, the chief of the Chehalis First Nation, Willie Charlie, was drift-netting on the Fraser River near the mouth of the Harrison River. As he prepared to deploy his net at a traditional fishing site, the sports fishers angling nearby moved out of the way, as they usually did, but this time there was one sports fishing boat that refused to move. Charlie’s net became entangled with the other boat’s gear, and a violent altercation ensued. “They threatened us and repeatedly rammed our boats as we fought to untangle our gear and defend ourselves with oars and poles,” said Charlie. “Some among the sport fishermen had drawn guns and knives as we fought to protect ourselves. I was shot in the face by a pellet gun, gear was damaged and words were exchanged before the sport fishers finally dispersed.” In the preceding week, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans had closed the river to sockeye salmon fishing, after millions of fish failed to return to the river to spawn. Fishing for Chinook salmon was still permitted according to federal fishing regulations, and for the Aboriginal food fishery large mesh drift nets had been approved for use in limited weekend openings. Stó:lō Tribal Council spokesman Ernie Crey voiced the serious concerns of the Stó:lō First Nation bands who depend on the Fraser River for salmon. “The Fraser River’s Aboriginal people are now engaged in a desperate struggle to catch and preserve salmon to avoid hardship this coming winter,” Crey said. He also raised concerns about ongoing attacks against the Aboriginal right to fish, and called on all fishers, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal to “respect the Constitutional priority of the food, social and ceremonial fishery.”1

During the salmon fishing season, tensions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers are commonplace on the Fraser River. Sometimes conflicts arise over the so-called Aboriginal “food fishery,” but more often non-Native fishermen oppose the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ program that allows some salmon caught by Stó:lō fishers to be sold commercially. Both the BC Fisheries Survival Coalition, a group of non-Native commercial fishers, and Prime Minister Stephen Harper, have called for an end to what Harper has termed “racially divided fisheries programs.”2 They argue that all Canadians should have equal access to the fishery, and that Aboriginal peoples should not have priority to fish for sale. This argument goes against concepts of Aboriginal rights. Environmentalists have different, but related concerns. They worry that there are too many fishers chasing too few fish. They wonder, if Indigenous peoples are a user group, or “stakeholder,” why don’t they make concessions in order to help conserve and share a common resource? In other words, can’t people just get along for the sake of the salmon?

Such reactions contain a number of problematic assumptions about the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the salmon, and sidestep important questions of Indigenous rights, Indigenous economies, and Indigenous histories (including the history of Indigenous-settler relations in the fisheries). Indigenous peoples are not “stakeholders;” they have conducted their traditional fisheries since time immemorial, and Indigenous harvesting practices have special status under Canadian law. For many thousands of years, Indigenous communities successfully managed the fishery without the help of the Canadian state. Most importantly, Indigenous peoples never gave up the right to manage the fisheries for their own benefit, which includes, but is not limited to, food, social and ceremonial purposes. For Indigenous peoples on the coast and far into the interior, salmon has always been a source of food, wealth, and trade, and is intricately tied to their continued existence as Indigenous peoples.

In this section, we will examine how the “food fishery” came to be, and how it has worked to conserve salmon for the benefit of the non-Native industrial fishery. We will explore how Indigenous fisheries management was replaced with state regulation, and the circumstances Indigenous fishers must still navigate in order to harvest fish from their ancestral fishing grounds: declining runs, increasing competition from sports and non-Native commercial fisheries, restrictions on gear types, fishing spots and openings, and legal precedents that define the Aboriginal right to fish for food. As part of our look at the rise of the food fishery and the difficulties Indigenous peoples face in gaining recognition of the right to sell fish commercially, we will also briefly examine the participation of Indigenous fishers in the industrial fisheries, and how they functioned alongside the traditional fisheries.

Fishing since time immemorial

When the first salmon canneries appeared on the BC coast in the 1870s, Indigenous peoples had already built flourishing economies based on salmon. The one-way spawning migrations of adult salmon to the stretch of river where they were born has always brought a crucial source of energy and nutrients from the ocean to freshwater and terrestrial environments, allowing people to preserve vast quantities of fish for winter use, and for trade with other Indigenous groups. Salmon were received by First Nations peoples as gift-bearing relatives, and were treated with great respect. Nick Claxton describes his community’s traditional reef-net fishery as a successful collaboration between the fish and the people:

The WSÁNEC people successfully governed their traditional fisheries for thousands of years, prior to contact. This was not just because there were laws and rules in place, and that everybody followed them, but there was also a different way of thinking about fish and fishing, which included a profound respect. At the end of the net, a ring of willow was woven into the net, which allowed some salmon to escape. This is more than just a simple act of conservation (the main priority and narrow vision of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans). It represents a profound respect for salmon. It was believed that the runs of salmon were lineages, and if some were allowed to return to their home rivers, then those lineages would always continue. The WSÁNEC people believe that all living things were once people, and they are respected as such. The salmon are our relatives. … Out of respect, when the first large sockeye was caught, a First Salmon Ceremony was conducted. This was the WSÁNEC way to greet and welcome the king of all salmon. The celebration would likely last up to ten days. … Taking time to celebrate allowed for a major portion of the salmon stocks to return to their rivers to spawn, and to sustain those lineages or stocks.3

As lineages or stocks, salmon populations are enormously diverse, with many different life-history adaptations, such as the length of time spent in freshwater and in the ocean, the timing of spawning, and age and size at maturity. In addition, since fat content decreases with migration distance, processing techniques, such as drying and smoking, needed to be closely adapted to individual runs. Local ecology and culture worked together to produce highly specialized salmon food products for food and trade. Wind-drying of salmon in the Fraser Canyon, for example, depended on the temperature and humidity conditions created by this upriver canyon environment. In early July, when hot, dry winds blew into the canyon, salmon were fished from particular, family-owned spots, and then hung on giant racks perched on rock bluffs, where they could be dried before the arrival of blowflies and wasps. 4 Despite government intervention, and changes in technology to fishing by boat with gill nets, the practice of wind-drying continues to this day among some Stó:lō families, and wind-drying is consciously regarded as a traditional practice in need of protection.5

Harvesting methods

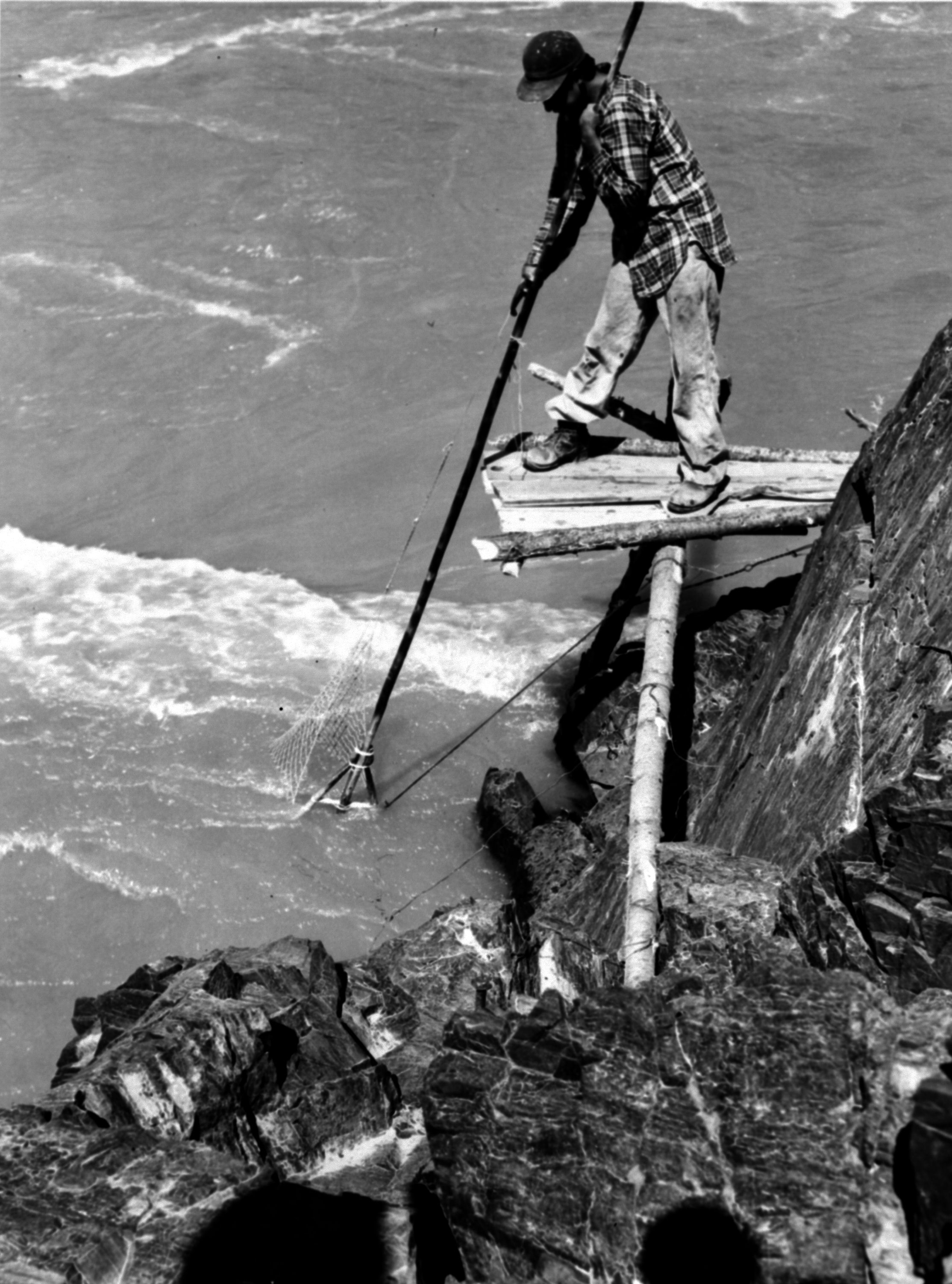

Fishing for salmon with a dip-net. Image D-06014 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives.

The practice of harvesting salmon on rivers in the traditional territories also allowed for local populations to carefully monitor the status of local salmon populations, share the runs with upriver groups, establish harvesting agreements between house groups from different territories, and develop sophisticated harvesting techniques. A variety of fishing gear enabled fishers to target different species and runs of salmon at the same site, as well as across sites that differed in their ecological and physical conditions. In the Fraser River canyon, fishers stood on rocky outcroppings or wooden platforms, expertly gaffing or dip-netting fish in the swirling eddies below. On relatively shallow, slow-moving tributaries, weirs were used to channel fish into traps, or towards fishers with other harvesting equipment. These fence-like structures often had panels that could be removed when not fishing, and had complex underwater channels and impounding pens. (See photograph of Cowichan fishing weir below.) Although weirs were once decried by cannery owners as “barricades” that prevented fish from reaching the spawning grounds, and are still considered illegal by DFO, some environmentalists today are looking to weirs and other stationary traps as examples of selective harvesting techniques that could help conserve endangered salmon populations. (See, for example, this Globe and Mail article from 2009.) Elsewhere along the coast, fish were taken in the tidal areas where salmon congregate near the mouths of rivers. At some locations, such as in Tlingit territory, stone traps were used to trap salmon at low tide; an arc of carefully positioned stones created shallow pools from which salmon could be selectively harvested by waiting fishers, who tapped the surface of the water behind the trap until the water level had dropped below the level of the stones.6 The Saanich, fishing in the waters off southern Vancouver Island and the San Juan Islands, set reef nets perpendicular to the shore in places, such as the mouth of a bay, where the tidal flow pushed salmon into the nets. These nets were made of willow and cedar. Dune grass threaded through the twining of the ropes made fish believe they were swimming safely close to the bottom. A team of highly experienced fishers was needed to build and operate weirs, traps, and reef nets safely and effectively. In addition, decisions about access to particular fishing spots were made by the elders of extended family groups, who also held the knowledge of the family’s history at, and ancestral rights to, that fishing location.7

Cowichan salmon weir. Image G-06604 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives

Indigenous fishing techniques were not only highly productive, but the timing and level of harvest was carefully regulated through systems of what we today would call “resource management.” Specialized technologies and processing techniques were developed to deal with very large quantities of fish. For example, in 1904 the federal fisheries officer for the Upper Skeena reported that the Babine were catching 500 to 600 salmon a day in their weir fishery, and that they had caught 750,000 salmon that year.8 One anthropologist estimated the annual pre-contact level of salmon consumption at 1,000 pounds per capita; with an immediate pre-contact Stó:lō population of 20,000 to 60,000 people, between 4 million and 12 million salmon would have been consumed annually, and this does not include fish harvested for trade, or for ceremonial purposes.9 Given these large harvests, why did depletion not occur?

The leaders of house groups, who had ancestral rights to particular fishing spots, served as stewards of the resource – making decisions about who could fish, how and when fishing would take place, and how many fish would be taken. In Stó:lō territory, for example, fishing spots were, and still are, family-owned. Stó:lō cultural historian Sonny McHalsie explains it this way:

The Sia:teleq was the person who was accompanied by the family to take care of the fishing ground and the access to it, so he was kind of like the co-ordinator of the ground. He wasn’t the owner because no individual could own it. But based on his knowledge of the extended family, his knowledge of the various fishing methods, his knowledge of the capacity of the dry rack, his knowledge of the capacity of the camp, of the number of children that extended families had, of the number of fishing rocks that were accessible according to the varying levels of the river – with all of that in mind, he was able to co-ordinate. “I’ll tell you who can fish now. You should be fishing these rocks now, and this is the number of sticks that you have. And because you have this many children you should be making sure you have this much fish put away.” So he kind of co-ordinated all that.10

Since fishing required the allocation and sharing of seasonal resources between families and tribes, fisheries management was not a distinct practice, separate from governance and law: it was integrated with systems of rank and privilege, distinct forms of production and exchange, including extensive networks of ceremonial redistribution and trade, and protocols for recognizing and transferring rights to fishing places. The writings of 20th century ethnographers such as Franz Boas and Wilson Duff provide important insights into the ways in which the potlatching system worked to ensure accountability in fisheries management as practiced by the Kwakwaka’wakw. Martin Weinstein, the Aquatic Resources Coordinator for the Namgis First Nation, examined the records of these early anthropologists, and concluded that the potlatch functioned as a “monitoring device,” through which the sustainability of a title-holder’s fishing practices was repeatedly assessed by members of the tribes who potlatched together. Potlatch goods were produced by a particular house group, or namima, from the territory’s own resources. If the flow of wealth from the territory of a namima declined, so did the rank of their chief. In addition, since rank and prestige were associated with distributing, rather than accumulating wealth, there was little danger of title-holders hoarding resources for their individual benefit.11

The introduction of canneries and a wage-based economy

These chiefly economies continued, and in many ways became the backbone of the burgeoning, late 19th century industrial economy. With the advent of canning technology, and the expansion of lucrative export markets for salmon, settler Canadians set up processing facilities on the major salmon-bearing rivers – the Fraser, Nass, and Skeena rivers – as well as at Rivers Inlet, and on Vancouver Island, the Queen Charlottes, and other locations. The growth in new canneries was staggering. In her book Tangled Webs of History, historian Dianne Newell reports that in the last decades of the 19th century, salmon canneries spread from the Fraser and Skeena rivers to all corners of the British Columbia coast. In 1901, the year of record sockeye runs for the Fraser River, 49 cannery camp-villages were operating from New Westminster to the mouth of the river.12 By the early 1900s, it was only the scarcity of labour and fish that slowed down the relentless pace of expansion.13

Indigenous fishers saw new economic opportunities in the industrial fishery – opportunities that could be combined with existing seasonal rounds and that were compatible with, and enhanced, Indigenous economies and forms of social organization. Anthropologists Charles Menzies and Caroline F. Butler write that “the northern canning industry was quite literally built upon the traditional fisheries of the Ts’mysen.”14 The operation of customary fishing sites had always been organized by extended lineage groups; fishing for sale to local canneries using drag seines contributed to the existing Indigenous economy, and occurred at places where other technologies, such as stone tidal traps, were formerly used. Menzies and Butler are careful to point out that such fishing sites were by no means defined by their links to the industrial fishery: not only were salmon harvested and preserved for home use, but other food items, such as other species of fish, as well as mountain goat, deer, cockles, clams, and berries were collected and prepared for winter use and for trade with other Indigenous groups.15 In some cases, entire villages relocated to canneries during sockeye fishing season in July and August, with only a few elderly people staying behind as caretakers: the Bella Bella, for example, often went to the Rivers Inlet canneries, where they were joined by people from Cape Mudge and Alert Bay; the Kitkatla worked at local canneries on the Skeena River, and the Fraser River canneries drew large numbers of Indigenous families from throughout the coast and as far away as the Upper Skeena river.16 This work, however, was only one of many seasonal activities, including fishing for other species of salmon, such as chum or pink salmon after the close of the sockeye fisheries; fishing and processing other species such as eulachon, or herring spawn; deep-sea fishing for halibut, hand-logging, hunting; and many other activities.

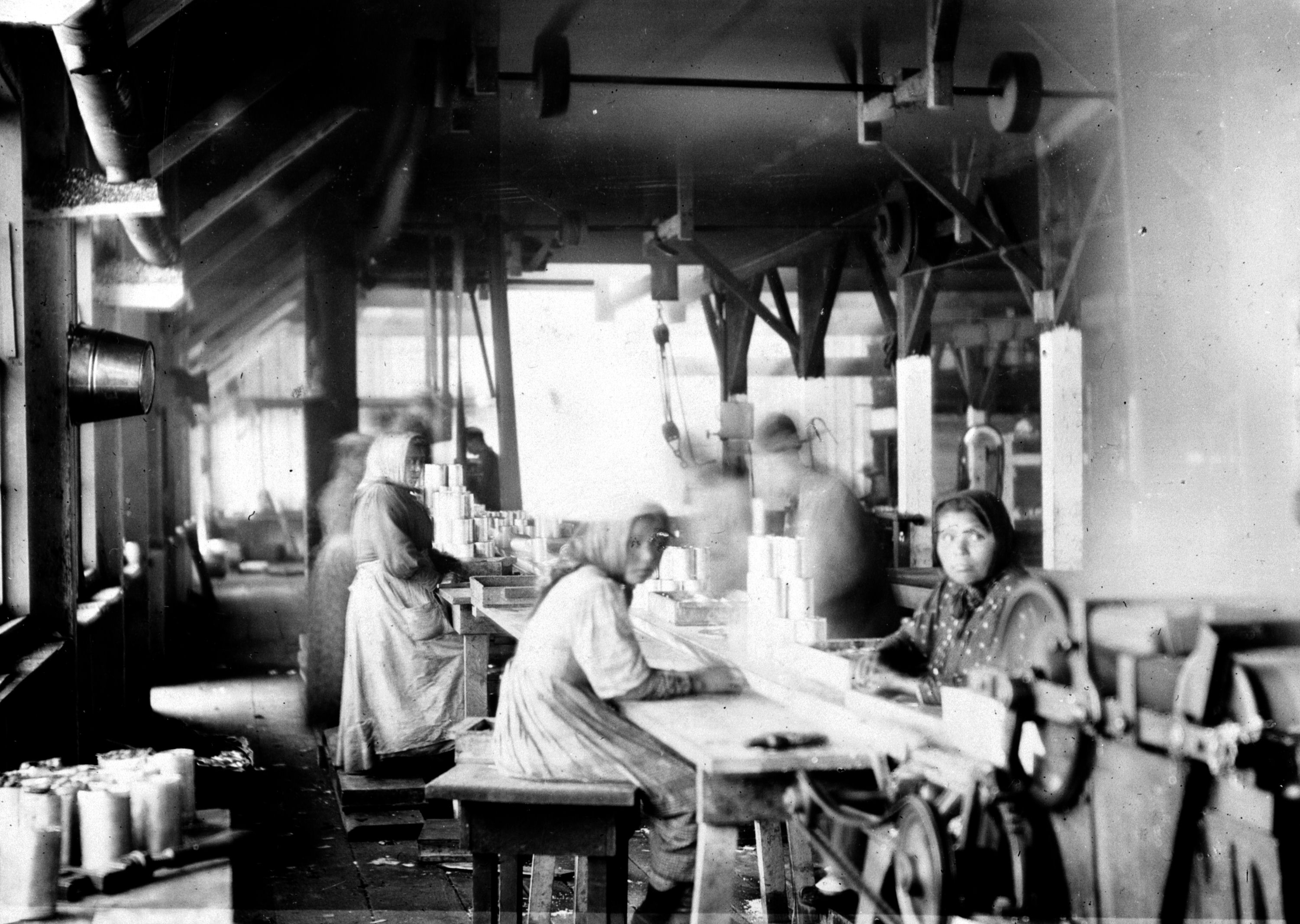

First Nations women working at Claxton Cannery. Image A-08198 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives.

Cannery operators considered Indigenous peoples to be at most “helpers” in the industrial fishery. As “helpers,” they were paid only for their labour, and not for the sale of their resources.17 Despite cannery operators’ attempts to marginalize Indigenous economic structures, the industrial fishery operated alongside an Indigenous economy, and people worked for these fisheries as members of house groups and communities, and not simply as individuals. Customary leaders served as labour recruiters for the industrial fishery, determining who went to the canneries, and even at which cannery they worked.18 Women, but also some children and elderly people worked washing, cutting, gutting fish and filling cans with great precision and speed. They worked hard for long hours, and were paid based on how many cases they could fill in a day. Their labour was in such high demand that canneries often hired Indigenous men to deliver fish to the cannery in order to guarantee the labour of thousands of women and girls in the canneries.19

In 1892, only 40 of more than 3,000 Indigenous fishers on the Fraser had “independent” licenses, or licenses that enabled them to catch fish independently from canneries.20 Independent licenses were generally unavailable to Indigenous fishers. By 1912, an openly discriminatory policy gave priority to so-called “bona fide white fishermen” on the north coast of the province. Since highly productive Indigenous fishing technologies were banned, and many Indigenous fishers did not have the capital or collateral necessary to buy their own boats, it was difficult to gain entry into the fishery. Many Indian agents denied Indigenous fishers licenses due to pressure from cannery owners objecting the economic independence such licenses would create.21 As the fishery began to centralize after World War II, and as larger boats with expensive technologies became common, limited access to financing made it increasingly difficult for Native fishers to remain competitive.22 Seine licenses were not available to Native fishers until 1924, as a matter of department policy, and by that time most of the seine licenses had already been allocated to non-Native fishers. Such marginalization of Indigenous fisheries from the industrial fishery may have had the unintended effect of strengthening traditional fisheries governance structures, yet reckless levels of industrial seining at the mouths of bays as well as log drives down salmon-bearing rivers destroyed freshwater salmon habitat and prevented the schooling fish from ascending the rivers. Hydroelectric development and the diversion of water for agriculture and municipal use severely damaged salmon spawning grounds. These destructive practices decimated the winter food supply of many tribes.23

The wages earned in the industrial fishery were an important source of cash in an increasingly mixed subsistence-wage economy. Credit and cash advances were readily available at the cannery store, which helped to ensure that fishers and plant workers would return the next year. Earnings from the canneries helped to pay for winter supplies, and also fed into the existing potlatching system, through which rights and responsibilities towards customary fishing grounds were recognized and affirmed. Goods and cash therefore entered into traditional systems of exchange, and the cannery itself became an important site of inter-tribal trade, where specialty fish, meat, and plant products were traded between women from different First Nations.

The creation of an Aboriginal “Food Fishery”

Despite the fact that Indigenous peoples were gradually being displaced from the fishery by other workers, colonial officials recognized that Indigenous people were enjoying a certain amount of success in using the industrial economy to support Indigenous economic practices and traditions. In submitting his annual report in 1910, the Indian Agent for the Kwawkwelth Agency, W. M. Halliday, complained about the difficulty in enforcing the law against the potlatch, and the fact that,

Up to the present for some years new work has been plentiful and good wages paid for it and this has taken away largely the ‘spur of necessity.’ Their native food which consists largely of the products of the sea and the rivers has generally been plentiful and easily obtained. Recently, however, the fishing regulations have been not only more strict, but are more strictly enforced, and it will soon happen that it will require more labour to satisfy their wants which will also be an important factor in making them more industrious.24

The fishing regulations to which Halliday refers were ones that restricted Indigenous fisheries to a food component only. This separation between fishing for food and fishing for trade and sale was artificial: it had no precedent in actual Indigenous societies. It also opened a space into which the state could insert its own management authority. The 1888 fisheries regulations specifically prohibited Indigenous fishing “by means of nets or other apparatus without leases or licenses from the Minister of Marine and Fisheries,” but indicated that “Indians shall, at all times, have liberty to fish for the purpose of providing food for themselves but not for sale, barter or traffic, by any means other than with drift nets, or spearing.”

The increasing non-Aboriginal interest in the fisheries, particularly with sport fishers, put pressure on the government to open up otherwise restricted Aboriginal fishing grounds.25 Government restrictions on Aboriginal fishing increased in the 1890s, and government officials eventually required Indians to acquire a permit to fish for food.26 Historian Douglas Harris suggests that the introduction of permits for Native food fisheries is significant in that it “effected the legal capture of the fisheries,” which, in parallel to the reserve system, regulated and limited Native access to resources while opening them up to the settler population.27

In the following years, Indigenous fishing was increasingly described by Fisheries officials as a privilege granted by the government. The Minister of Fisheries, Charles Tupper, described the food fishery as a “valuable privilege:” “Such permission is not to be considered as a right but as an act of grace, which may be withdrawn at any time.”28 As time went on, the regulations of Native fisheries increased. In 1917, new amendments stipulated that food fishing permits would be subject to the same closed seasons, area, and gear restrictions as the non-Native commercial fishery.29 The colonization of the fisheries was now complete: the production of fish had been separated from the management of the fisheries, and that management had been transferred to the Canadian state. Indigenous needs and uses were now arbitrarily categorized and highly regulated, and the colonial goal of enabling settler access to fisheries was achieved. As Harris has suggested, while regulations were to limit “the food fishery to that which could be consumed by the fisher and his or her family… the goal of officials within Fisheries was to eliminate that fishery as well if it were possible.”30

Indigenous peoples did not accept this state of affairs, and continued to assert that they had never willingly given up jurisdiction over their fisheries. On the Nass, for example, the Nisga’a at Kinconlith refused to buy fisheries licenses, since, as far as they were concerned, fishing on the river was subject to Nisga’a law, not Dominion law. They therefore insisted that license fees collected by Fisheries officers belonged to them.31 At many other locations on the coast, Indigenous people refused to give up their fisheries. When Fisheries officials attempted to destroy the Babine salmon weirs for the third year in a row in 1906, they were met with stiff resistance from the Babine. The Babine were determined to defend their weirs and refused to repeat the previous year’s failed experiment with donated nets. Indigenous communities did not see cannery work as compensation for the loss of their fisheries, and continued to insist that they had a commercial right to fish without interference from Fisheries regulations.

In the early 1900s, cannery owners at the mouths of the Skeena, the Nass, and the Fraser continued to press the federal fisheries department for restrictions to Native fishing, and for the destruction of Indigenous fishing technologies, particularly weirs, which they claimed were “barricades” that prevented fish from reaching the spawning grounds. In years of poor salmon runs, the blame for overfishing fell particularly heavily on Native fishers. In 1913, a rock slide at Hell’s Gate occurred during blasting for construction on the Canadian Northern railroad. The slide – a “barricade” of massive proportions — destroyed major canyon fishing sites and permanently damaged the sockeye and spring salmon runs above them. Salmon could not pass through the debris. The immediate response of the Fisheries department was to ban all net fishing in inland waters. As a result, Aboriginal fishers bore the brunt of this conservation effort. The bands above the slide – the Thompson, Shuswap and Lillooet – all fished with nets, and this restriction was clearly directed at the upriver Native fisheries. Soon thereafter, all Native fishing between Hope and Lytton was banned, and, for the first time, restrictions against selling fish were strictly enforced. All the while, the non-Native fishery at the mouth of the Fraser remained open.32

Food fishing licenses were usually restricted to Indigenous peoples considered “deserving”: “old and needy” Indians who had no other way to sustain themselves.33 Those who worked for wages, lived close to “civilization,” or whose ancestral fishing grounds were at spawning grounds or hatcheries were not permitted to fish for food.34 While reserves were intended to guarantee Indigenous access to the fisheries, the Department of Fisheries has never recognized these exclusive Indigenous fisheries. In addition, Indian reserves located at seasonal fishing spots did not ensure access to the salmon fisheries, and in many cases the inlets just outside the reserves had been leased for fishing to canneries and other non-Native fishing companies.

Sparrow, Van der Peet, and other legal challenges

In 1984, the Musqueam band decided to challenge the restrictions that had been placed on their food fisheries in the name of “conservation.” Ron Sparrow was arrested for fishing on the Fraser River with a drift net that was longer than the length specified by the band’s food fishing license. He raised an Aboriginal rights defence, stating that the net-length restriction was inconsistent with Aboriginal rights, which were recognized by section 35(1) of the Constitution Act of 1982. Although Sparrow was convicted at trial, the case was appealed to the Court of Appeal, and eventually to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1990. The Department of Fisheries argued that Aboriginal rights to fish had been extinguished by the detailed regulations contained in the Fisheries Act, and that the net-length restriction was necessary for conservation. The Supreme Court of Canada found that Aboriginal rights had not been extinguished simply because they were regulated in great detail, and it rejected the “public interest” justification for limiting Native fisheries as vague and unworkable. While it accepted “conservation” as a valid objective, the court also acknowledged that, given the limited nature of the resource, conflicts of interest between users were inevitable. The court stated that these conflicts could be resolved only through a clear priority scheme, in which Aboriginal fishing for food, social and ceremonial purposes – the so-called “food fishery” – had first priority, after the demands of conservation had been met. Conservation cannot be used to conserve the fish for other users. The court therefore overturned the conviction, and the case remains one of the most important court decisions for Aboriginal peoples across Canada.35

Despite the victory for Aboriginal rights to fish for food, the right to fish for food is the subject of intense regulation by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Restrictions on these fisheries include limits on what kind of gear can be used, the hours and days during which the gear can be deployed, and the particular species that may be targeted. [link to table of DFO ceremonial fisheries openings] Aboriginal fishing also requires a license from the Department of Fisheries, and this interferes with Indigenous forms of management and ownership of salmon. Sonny McHalsie explains the effect of licenses on fishing practices in Stó:lō territory:

Ownership of fishing grounds is through family. But then you wonder, why do people look at ownership as individual then? What happened there? And then I started to understand, well, back in the late 1800s the Fisheries Act was created and all these different laws were made that didn’t allow our people to sell fish any more. They said that only saltwater fish could be sold and that it is illegal to sell anything caught in fresh water. So they took away our economy and, not only that, they wanted to start regulating our fishing. So they imposed the fishing permits on our people. What’s on the fishing permit? It doesn’t talk about the extended family or family ownership. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans didn’t take into consideration the fact that we had our own rules and our own regulations about who has access to fishing grounds and who fishes where. We have our own protocols and our own laws. Instead, they imposed a fishing permit that had an individual’s name on it. And it said that individual could fish from such and such place to such and such place. So it’s almost as though it is wide open: you can fish anywhere in there. So right away they ignored our own laws and protocols of where to fish. It took the all-encompassing perspective of ownership of fishing grounds – our wide perspective of it – and narrowed it to an individual perspective. So that a lot of our fishers now, up in the canyon, look at their fishing spot as their own. I’ve heard some of them say, ‘It’s mine and only mine.’ And ‘No one else can fish here, not my brothers not my sister, not my mom or my dad. That is my spot.’ I couldn’t believe it when I heard one of the fishers say that. That’s how some of the fishers think. So they have to change that again.36

A commercial right – the right to sell fish – is still the biggest hurdle for Indigenous access to the fisheries. In 1995, Dorothy Van der Peet, a Stó:lō woman, was arrested for selling 10 salmon caught under a food-fishing license. She was found guilty at trial, and the Appeals court and Supreme Court of Canada upheld the conviction. In the words of the majority decision of the Supreme Court, Van der Peet had “failed to demonstrate that the exchange of fish for money or other goods was an integral part of the distinctive Stó:lō culture which existed prior to contact and was therefore protected by s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.”37

Indigenous peoples in British Columbia have nevertheless continued to sell salmon. Crisca Bierwert draws parallels between such sales to historical underground potlatching activities during the potlatch ban era and therefore sees outlaw fishing as covert practices that are important assertions of agency, “as crucial to the histories here as they were to the longhouse dancers at one time.”38 However, despite the economic and cultural importance of outlaw fishing, low-grade harassment on the fishing grounds makes such resistance difficult . (See, for example, this press release regarding one such incident involving a St’at’mic elder in 2004.) Following the Sparrow decision of 1990, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), concerned about its legal obligations, initiated a pilot sales program through which bands that sign agreements with DFO are allowed to sell some fish caught under food fishing licenses. This program allows the DFO to provide “benefits” to Indigenous fishers, in the form of licenses and exclusive commercial openings, in exchange for continued management control over Indigenous fishing. You can read about the DFO’s Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy here.

“First Nations are being allocated fishing rights not because of their race but because their fisheries were wrongfully appropriated …

If a First Nation is recognized as having fishing rights above and beyond the food fishery it will be because it has either established a constitutional right to such a fishery in court (as the Heiltsuk have done with respect to the commercial herring spawn-on-kelp fishery) or because it has negotiated such rights as a side agreement to a treaty.

Either way, historical entitlement is the basis of the agreement, not “race,” because simply being “Indian” is not enough. An aboriginal person who is not a member of the treaty group can no more participate in a treaty fishery without permission than a non-aboriginal person can.

Surely there is something very unfair about taking property away from people because of their race and then arguing that it is racist to give it back.”

Hamar Foster,

Professor of Law,

University of Victoria

Not a “race-based” fishery

In 1998, a group of non-Native fishermen took to the water during an Aboriginal-only opening on the lower Fraser River that had been negotiated by the Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Burrard First Nations under a pilot-sales agreement. The non-Native commercial fishers said they were protesting a “race-based” fishery, which violated equality guarantees in the Constitution. The BC Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada rejected this argument. As we have seen in this section, Indigenous fisheries are not race-based, nor were they created or “granted” by the Canadian state. Indigenous communities used and managed the salmon fisheries as distinct political communities long before the British assertion of sovereignty. The creation of the food fishery by the federal fisheries department, however, served to separate Indigenous communities from the wealth of their salmon resources while conserving them for the non-Native commercial fishery. When Indigenous people worked for wages in the industrial fishery, they integrated this seasonal employment into their mixed cash-subsistence economies, but this did not pay for the sale of the resources – nor did Indigenous communities ever give up ownership or management control of their salmon runs. Confrontations on rivers and coastal fishing grounds, such as the one on the Fraser River last summer, therefore represent ongoing conflicts that have deep historical roots.

Recommended Resources

“Native groups want sport fishing ban after shooting.” The Canadian Pres, August 18, 2009. https://www.ctvnews.ca/native-groups-want-sport-fishing-ban-after-shooting-1.426462

Bierwert, Crisca. Brushed by Cedar, Living by the River. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999. 232.

BC Elders Communication Centre Society, “Elders’ Voice,” Volume 6 Issue 10, September 2006, 11. Available online at: http://bcelders.com/Newsletter/Sept06.pdf

Butler, Caroline. “Regulating Tradition: Sto:lo Wind Drying and Aboriginal Rights” (M.A. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1998).>

Claxton, Nicholas Xumthoult, “ ISTÁ SĆIÁNEW, ISTÁ SXOLE: ‘To Fish as Formerly:’ The Douglas Treaties and the WSÁNEĆ Reef-Net Fisheries.” In Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Resurgence, and Protection of Indigenous Nations, ed. Leanne Simpson (Winnepeg, Arbeiter Ring, 2008), 52-55.

Carlson, Keith Thor. “History Wars: Considering Contemporary Fishing Site Disputes,” in A Sto:lo Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001), 58.

“Reconciliation, partnerships and Indigenous fisheries” Accessed December 22, 2020. Available online at: https://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/abor-autoc/index-eng.html

Harris, Douglas. Fish Law and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

Landing Native Fisheries: Indian Reserves & Fishing Rights in British Columbia, 1849-1925. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Harris, Douglas C. And Millerd, Peter. “Food Fish, Commercial Fish, and Fish to Support a Moderate Livelihood: Characterizing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights to Canadian Fisheries.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 1 (2010): 82-107. Available online at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1594272

Menzies, Charles and Caroline Butler, “Returning to Selective Fishing Through Indigenous Fishing Knowledge,” American Indian Quarterly 31, 3 (2007): 451-452.

Menzies, Charles and Caroline Butler, “The Indigenous Foundation of the Resource Economy of BC’s North Coast, Labour 61 (Spring 2008): 143.

Naxaxalhts’i, Albert (Sonny) McHalsie, “We Have to Take Care of Everything That Belongs to Us,” in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce G. Miller. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007.

Newell, Dianne. Tangled Webs of History: Indians and the Law in Canada’s Pacific Coast Fisheries (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 1994.

Muszynski, Alicja. “The Creation and Organization of Cheap Wage Labour in the British Columbia Fishing Industry.” PhD Dissertation, University of British Columbia, 1986.

R G-10, Vol. 12338, Indian Agent’s Letterbook, 1908-1911, p. 612.R. v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507.

Smith, David A. “Salmon Populations and the Sto:lo Fishery,” in A Sto:lo Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001), 120.

Ware, Reuben M. Five Issues, Five Battlegrounds: An Introduction to the History of Indian Fishing in British Columbia 1850-1930. Coqualeetza Education Training Centre, 1983. 30-32

Weinstein, Martin. “Pieces of the Puzzle: Solutions for Community-Based Fisheries Management from Native Canadians, Japanese Cooperatives, and Common Property Researchers,” The Georgetown International Environmental Law Review 12 (2000): 375-412.

Endnotes

1 “Native groups want sport fishing ban after shooting.” The Canadian Pres, August 18, 2009. https://www.ctvnews.ca/native-groups-want-sport-fishing-ban-after-shooting-1.426462

2 http://bcelders.com/Newsletter/Sept06.pdf

3 Nicholas Xumthoult Claxton, “ ISTÁ SĆIÁNEW, ISTÁ SXOLE: ‘To Fish as Formerly:’ The Douglas Treaties and the WSÁNEĆ Reef-Net Fisheries.” In Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Resurgence, and Protection of Indigenous Nations, ed. Leanne Simpson. Winnepeg, Arbeiter Ring, 2008. 54-55.

4 Keith Thor Carlson, “History Wars: Considering Contemporary Fishing Site Disputes,” in A Sto:lo Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001. 58.

5 Caroline Butler, “Regulating Tradition: Sto:lo Wind Drying and Aboriginal Rights.” M.A. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1998.

6 Charles Menzies and Caroline Butler, “Returning to Selective Fishing Through Indigenous Fishing Knowledge,” American Indian Quarterly 31, 3 (2007): 451-452.

7 Claxton, “To Fish as Formerly,” 52-55.

8 Douglas Harris, Fish Law and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001. 96.

9 David A. Smith, “Salmon Populations and the Sto:lo Fishery,” in A Sto:lo Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001. 120.

10 Naxaxalhts’i, Albert (Sonny) McHalsie, “We Have to Take Care of Everything That Belongs to Us,” in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce G. Miller. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007. 97-98.

11 Martin Weinstein, “Pieces of the Puzzle: Solutions for Community-Based Fisheries Management from Native Canadians, Japanese Cooperatives, and Common Property Researchers,” The Georgetown International Environmental Law Review 12 (2000): 375-412.

12 Dianne Newell, Tangled Webs of History: Indians and the Law in Canada’s Pacific Coast Fisheries Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994. 71.

13 Newell, Tangled Webs, 73.

14 Menzies and Butler, “Returning to Selective Fishing,” 446.

15 Menzies and Butler, “Returning to Selective Fishing,” 447.

16 Newell, Tangled Webs, 54

17 Newell, Tangled Webs, 53, 77.

18 Newell, Tangled Webs, 54

19 Newell, Tangled Webs, 86, 109

20 Newell, Tangled Webs, 77

21 Newell, Tangled Webs, 77.

22 Newell, Tangled Webs, 122-147.

23 Charles Menzies and Caroline Butler, “The Indigenous Foundation of the Resource Economy of BC’s North Coast, Labour 61 (Spring 2008): 143; Harris, Fish, Law, and Colonialism, 143-144; Newell, Tangled Webs, 89.

24 RG-10, Vol. 12338, Indian Agent’s Letterbook, 1908-1911, p. 612.

25 Douglas Harris, Landing Native Fisheries: Indian Reserves and Fishing Rights in British Columbia, 1849-1925. (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 107.

26 Harris, Landing Native Fisheries, 110.

27 Harris, Landing Native Fisheries, 111.

28 Harris, Fish, Law, and Colonialism, 71.

29 Newell, Tangled Webs, 96.

30 Harris, Landing Native Fisheries, 115.

31 Harris, Fish, Law and Colonialism, 63

32 Rueben M. Ware, Five Issues, Five Battlegrounds: An Introduction to the History of Indian Fishing in British Columbia 1850-1930 (Coqualeetza Education Training Centre, 1983), 30-32; Newell, Tangled Webs, 117.

33 Harris, Landing Native Fisheries, 121.

34 Newell, Tangled Webs, 117-119.

35 R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075

36 McHalsie, “We Have to Take Care of Everything,” p. 97.

37 R. v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507

38 Crisca Bierwert, Brushed by Cedar, Living by the River (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999), 232